I’ve been using Windows full-time at home for about ten months following many, many years of exclusive macOS use. In this post, I will tell you all of the things I like and dislike about Windows as a full-time desktop operating system for both casual use and more serious photography and software work.

Within this post, you can expect to find:

-

Unvarnished opinions of both Apple and Microsoft

-

Light cursing

-

Too many words

A forewarning: this post is really long, which is why I’ve provided a table of contents. Please feel free to read the part(s) that interest you, my feelings won’t be hurt, I just wanted to vent anyway.

Let us begin.

Why did you do this to yourself?

I just realized that I never wrote about this. I tweeted about it, though.

I actually built this thing in late March and as soon as it booted successfully I stopped using my MacBook Pro as my primary computer at home. Right off the bat, this system has delivered on its purpose: it’s fast as all get-out, and it’s nice to be able to edit huge images in Photoshop without any perceptible lag.

But it’s not all sunshine and rainbows in Windows world, and that’s what I really want to talk about, so let’s open the can and count the worms.

What’s the matter with Windows?

Where should I even start? I can bundle the issues I’ve had with Windows into the following categories:

-

Display and graphics problems

-

Human interface problems

-

Development environment problems

The things that annoy me most in the “display and graphics problems” category are going to be focused on that which affects visual work, which in my case is photography and design.

Development environment problems are going to feel familiar to most of you who came to this blog originally because I have written at length about software development concerns, Emacs, and so forth. I will get into some of that here.

I do run Emacs in Windows, and I have managed to get it working pretty well.

Display and graphics problems

I’ll talk about two broad issues: display artifacts and color profiles.

Display artifacts

If you’re a long-time Mac user and you start using Windows daily, the first thing you’re going to notice is that the display–and by that I mean how everything appears to you and moves around on the screen–doesn’t feel as “rock solid” as macOS.

In the macOS world, nothing flickers and nothing jumps or staggers. Not so in Windows, which to this day suffers from jagged animation, flickering, and other such visual artifacts, which you would think could have been resolved over the past several decades of incredible GPU advancements.

As an example, Windows 10 introduced “Task View,” which is as close to a total rip-off of Exposé as you could probably get without being sued for it, with the notable exception that every time you open it, windows flicker and jerk around like a high school animation project.

I don’t know enough about how this all works to explain why, but I can tell you that macOS is all GPU-accelerated and it’s smooth and consistent and beautiful all the time. Windows is inconsistent, choppy, and weird, which is how it’s always been, even with my GeForce RTX 2060, which is by all accounts ridiculously overpowered to move windows around on a screen.

All of this is tolerable, it is not a deal-breaker for me if windows very occasionally flicker a tiny bit, or move around in odd ways.

Color profiles

What had me deeply questioning my decision to move to Windows is the way Windows manages color profiles. Quick overview for the uninitiated: a color profile is simply a mapping of color numbers to other color numbers. Its purpose is to ensure that color numbers stored in files (like, say, photographs) are displayed accurately by a specific device.

It is extremely important to view photographs using a proper color profile because every monitor has different capabilities, and even individual displays of the same make and model will have slight manufacturing differences. You can generate a color profile using a device that sends pixels to your display and reads them with a colorimeter, noting the differences.

In macOS, you open your Display Preferences and you add a color profile file and you click OK. That’s it. Your color profile is now applied.

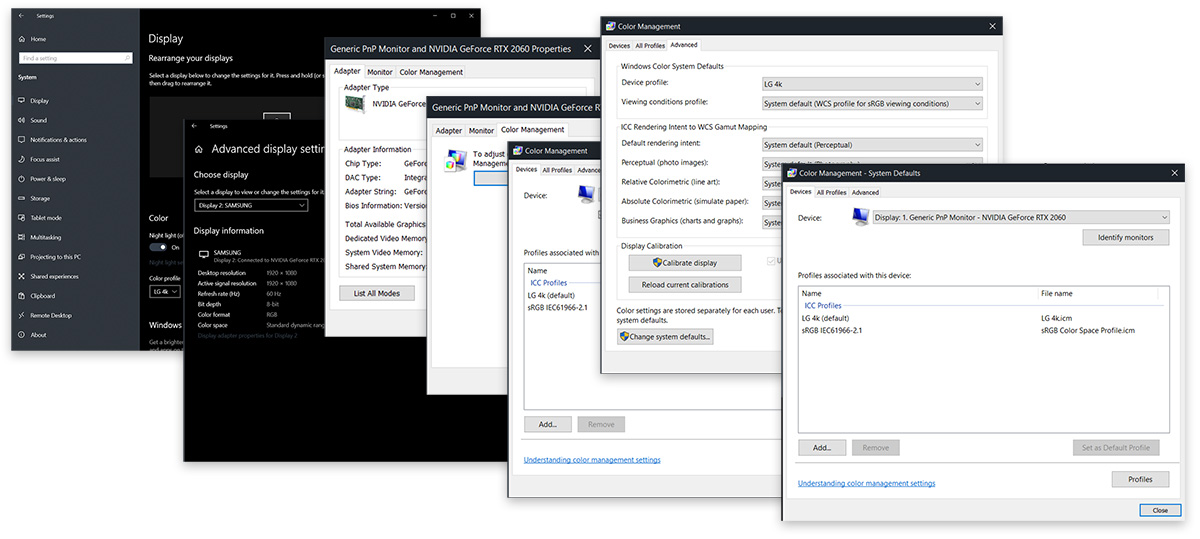

In Windows, you open Settings and choose Display and find the “Color profile” menu, but your new profile isn’t installed and there is no button to do that, so you find the link to “Advanced display settings,” which shows you some details about your monitors, and that doesn’t have anything on it about color so you click the link for “Display adapter properties for Display 1” and that opens a separate “old-school” properties window for your display adapter, and then you see a tab called “Color Management” so you click that, which presents you with one button that reads “Color Management…” so you click on that, and finally you get to the “Color Management” control panel.

Here you will find a list of profiles associated with your adapter/monitor, so you click “Add…” and you choose the file and you add it and you click “Close” and you’re done!

Except that your profile visibly turns on and off at random, like when the display wakes from sleep often the profile is not applied, or perhaps after restarting, or sometimes when a browser wishes to play DRM-controlled video streams, like on Netflix for example, the profile will turn off and on, or just off, or whatever it wants to do.

Some of these things can’t be stopped. The DRM-controlled video one in particular seems to toggle output to various displays when it turns on, and I haven’t figured out what to do about that other than deal with it.

If you want to really keep your color profile applied, though, you can set it as the system default, which means going back into the Color Management control panel, opening the “Advanced” tab, clicking the “Change system defaults…” button (which requires escalated privileges of course), and doing the same thing you did originally to add the profile file to the list.

After doing that, you can reset your “local” settings to the system settings, and that seems to help keep it from turning off randomly, most of the time.

Why is any of this necessary? Why is there even an “Advanced” tab here with so many different options? Somehow the Mac has none of these settings and nevertheless is still used exclusively by virtually all creative professionals. It seems to work OK for them.

Human interface problems

I suppose display and graphics problems are part of the “interface,” but here I want to talk about the physical interface and the semantic interface.

Again, there are two broad categories here that irk me the most: Windows trackpads suck unrepentantly, and Windows Explorer is kind of a mess.

Windows trackpads suck unrepentantly

The elephant in the room when it comes to physical Windows interfaces is the unavoidable fact that Apple makes the world’s best trackpads. A better trackpad never before existed, and has not existed since.

So what is it about the Apple trackpad that’s so damned good? Do they simply have unparalleled engineers on their team? Did they invent some new capacitive interface for which they own and tightly control numerous patents? Is the “Taptic Engine” actually alien technology that only Apple has succeeded in harnessing?

Well, yes and no. Apple definitely has some of the best engineers in the business, and the build quality and feel of their trackpads, as objects of industrial design, are evidence enough of that. But none of this technology is unique or mysterious at this stage of the game.

Capacitive touch surfaces that are able to register multiple touch points and motions simultaneously are everywhere now. Every single phone screen made in the last, what, 20 years, has such an interface.

The “Taptic Engine” is an Apple-patented implementation of a novel electromagnetic linear actuator that is a broadly known mechanism today, and in fact, Google Pixel phones now use the same technology for haptic feedback and vibration, as do many others.

So what this would seem to suggest is that either no company making Windows-compatible hardware has engineers even half as good as Apple’s, or there’s something else going on.

And, in fact, there is something else going on.

What’s really happening here, what you’re actually seeing and feeling when you use a Mac trackpad, is the thoughtfully designed and perfectly executed convergence of hardware and software. The hardware, which as I’ve said is absolutely best-in-class, is sending event signals to an operating system that was designed to work with it, whose sole purpose is to make each of your finger motions feel as if you’re physically touching the thing on the screen that you are moving.

It’s truly magnificent.

So, why do trackpads in Windows suck so hard? Why is it so difficult to make this happen in the Windows OS? The answer is three words: Windows Precision Touchpad.

You see, things actually used to be much worse. When we first started adding scroll wheels to mice, peripherals were connected to our computers with special serial ports called “PS/2” ports, and they talked to the computer in synchronous serial channel language. When you moved the scroll wheel up or down, the mouse send a command “scroll up” or “scroll down.”

If you scrolled the wheel continuously, the mouse sent a series of “scroll up” or “scroll down” messages, and lo, your webpage scrolled, haltingly, as your mouse’s wheel clicked through each discrete detent in its wheel.

Then, eventually, we were graced with the advent of the Universal Serial Bus, and ultimately the Human Interface Device (or “HID”) specification. Now you could plug nine mice into your computer if you wanted to and they could all work at the same time, if you were into that sort of thing.

But what didn’t change was the fundamental API. The discrete scroll events. Even though mouse movement events were always streamed rapidly so that your cursor could smoothly traverse the screen, and USB provided even more bandwidth for streaming data in parallel, the mouse wheel thing never changed.

At some point, though, it did change, and the change likely coincided with the rise of capacitive touch devices, trackpads in laptops, graphics tablets, and so forth. Windows needed a better way to talk to these new devices, to provide the sort of “continuous scroll event” facility that customers expected.

So Microsoft partnered with Synaptics, a maker of capacitive touch devices and software, and incidentally the engineers behind the original iPod’s capacitive click wheel, and implemented what they call the Windows Precision Touchpad driver. I wasn’t able to confirm this, but I’m pretty sure Synaptics did most of the work on the spec and Microsoft just wrote the Windows API around it.

Now, Windows has the ability to receive continuous scroll events. When a device uses the Precision Touchpad interface, it sends hundreds or thousands of events per second for movement and scrolling.

But, the thing is, and this is really where the rubber meets the road here, it still totally sucks! I mean, if you’ve ever used a trackpad on any Windows laptop, you understand me here. Compared to the way it feels to scroll and pinch and multi-finger swipe on Mac laptops, these Windows-compatible trackpads might as well be a series of strings that you pull on to move the cursor around.

(For those who don’t get the joke, the picture above is Mr. Bean driving his car from the roof by pulling on a rope he tied to the steering wheel and using a mop handle to press on the pedals. This is what it feels like to use a Windows-based trackpad in 2020).

What I’ve found along my Windows journey here is that the only viable pointing device for Windows is a goddamned mouse. Even the most expensive, well-designed Windows-compatible trackpads (and I’m looking at you, Logitech Wireless Rechargeable Touchpad T650, which retails on Amazon for over two hundred dollars) provide a daily use experience similar to driving a John Deere riding mower to work on the highway: it works, and it was expensive, but it makes you angry and people laugh at you for it.

So yeah, it’s 2020, and capacitive interfaces have existed since at least 1999, and Windows is made by the single largest software company on the planet Earth (market cap of $1.3 trillion at the time of this writing; Apple isn’t considered strictly a software company, but even if they were, Microsoft would still be number two) and I might as well mention at this point that Microsoft does actually make hardware now, too, but they can’t for the life of them make a good trackpad.

Windows Explorer is kind of a mess

Explorer is another one of these examples of organic growth and design-by-committee that stands in such stark contrast to Apple’s more minimalist and restrained UI approach.

There is so much to say about Windows Explorer, but instead of going into minute detail about how the “ribbon” sucks, how functions are available via multiple interface elements simultaneously viewable, and how context-sensitive help is implemented through baked-in Bing searches, let me try to boil down my complaints into one general thought.

Every time I open a new Explorer window, which is the primary interface into the content stored on my PC, I feel like I’m digging through my “junk drawer” looking for that one little thing that I knew I had a while ago and I just can’t remember where I put it and if it’s anywhere it’s got to be in here but what on Earth is all of this stuff anyway??

You see, navigation design is similar to organizing a kitchen. When you’re getting ready to make some food, you know that if you’re in front of the stove, you can reach over to the left and open that drawer and find your knives and spoons inside.

One of the fundamental efficiencies of the human condition is muscle memory and spatial awareness. We exploit these innate abilities to build habits, which make our lives easier day to day. Imagine if every time you opened the drawer to the left of the stove, there was something different in it. That would be annoying, wouldn’t it?

What macOS and iOS get right is that navigation and organization within apps always expresses the notion of consistent relativity. If you’re looking at the contents of your Desktop folder, that folder is always within your user’s “home” folder. It always appears within that context in the UI. If you click a “favorite” in the left bar, you see the contents of that favorite and its location relative to where it actually is, in its single, canonical place.

Windows plays pretty loose with these concepts. There is a way to set up the left panel where you can actually see a “Desktop” directory nested within another “Desktop” directory, because one of them isn’t actually a directory, it’s just a navigation tree node called “Desktop.” None of this makes any sense.

“Quick access” is a nice idea, but when you click an item there, it actually whisks you away to the item’s actual location. That seems like an honest thing to do, but it is annoying when you mis-click an item and now you’re five pages down a huge scrollable left panel and you need to scroll your shitty mouse scroll wheel up 30 times to get back to where you were.

These little minor punishments that you receive from Windows throughout your workday build up until you wonder whether it would have been worth the $5,000 you’d have to spend to get a Mac that performs just as well.

Development environment problems

Let me first, as a brief departure from the vitriol, say that I think Microsoft is doing some great things to better embrace the modern developer as they exist today. Rather than assuming that any developer who wishes to feast from Microsoft’s horn of plenty will immediately learn a .NET language and become a Visual Studio convert–a misconception they seem to have held for many years–Microsoft is finally implementing solutions to meet developers where they are.

These are in the form of Windows Subsystem for Linux (or “WSL”), and the development of the Linux- and macOS-compatible .NET Core.

On top of that, they released Visual Studio Code for every platform, and people really like it. This right here is an example of an established, competent software company doing a really good job at something everyone should expect them to do a good job at.

Nevertheless, they still have a ways to go, and where they fall short for me is in these two categories:

WSL is good, not great

Windows Subsystem for Linux is a phenomenal idea. In my day-to-day use of Windows, WSL gives me a lot of what I missed from macOS. But… It’s not quite there yet.

Now, I am running WSL version 1, because I refuse to move my system onto the developer pre-release track of Windows and risk everything just breaking one day, so it is possible if not likely that WSL version 2, which is already out there being beta-tested, fixes some or all of these problems, although I remain skeptical.

What WSL gives you in essence is a Linux system in a bottle, which can interact with the “stuff” on your computer fairly directly in most cases. The WSL system itself, the Linux system files, your WSL home directory, and all of that, are stored in a pretty deeply buried directory structure and I am told that accessing and modifying those files from Windows is likely to break WSL completely. But, you can reach Windows files from within WSL very easily.

Likewise, you can run a webserver within WSL, and you can connect to it from your Windows native browser the way you would in macOS.

Where things get weird is the issue I mentioned above; you can’t reach WSL files from Windows programs. Let’s imagine that you want to work on a Node.js application, so you want to use Visual Studio Code (or some other Windows-native editor, like, say, Emacs) to edit the code, and you want to run the development server on the command line.

Your only choice is to place your project files in a Windows directory and access them in WSL through the automatically mounted local drives. This works, but, bear in mind that these files are now stored on (probably) NTFS, which means they have no reasonable Linux permissions or ownership, and they might get saved with Windows line endings.

Granted that those problems are more or less endemic to developing anything in Windows, but the promise of a nice, sane, Linux-based development environment that gives you the same ergonomics as macOS is, as yet, unfulfilled.

A different solution could be to store the code in WSL and edit it with programs inside of WSL, like Vim or Emacs in the terminal. Obviously with this approach you lose out on some of the GUI niceties, but perhaps those aren’t important to you anyway. Using a pure WSL approach, everything stays Linux-like, and your collaborators would be none the wiser. This is a great solution overall because WSL is faster and lighter than a whole Linux VM.

Filesystems are hard

Coming back to this interop between WSL and Windows, the core issue that may not

even be solvable is that NTFS is entirely different from the ownership and

permissions architecture of Linux, so what typically happens is that you create

or modify a file in Windows and suddenly it’s got permissions of 0777.

Ownership is similarly non-portable, so you may end up with strange owner and group values, but of course none of that matters since all permissions are granted to the entire world.

WSL version 2 promises to fix a lot of the disk IO speed problems that have plagued WSL version 1, although I haven’t personally felt the pain there. I do feel pain when Emacs wants to do operations across a large number of files stored on NTFS, operations that (on the same files, with the same Emacs configuration) take a fraction of the time on HFS+. These are limitations to the heavy NTFS architecture and are extremely unlikely to ever get resolved.

Conclusions

Well, that was cathartic.

So what’s the take-away, here? Is Windows a non-starter for anyone who wasn’t raised on it? Does Apple still have a corner on the market for well-designed computers? Am I, personally, going to suffer chronic ulcers from the amount of Windows-induced stress I carry around daily?

If you asked me right now if you should switch to Windows from macOS, I would say “not if you can help it.” If you are someone who is productive and happy using macOS, switching to Windows is going to bring you nothing but agony and frustration. It is truly second-rate as a home-user system. It carries with it the burden of decades of scope creep and the requirements of “enterprise” customers with complex and unique problems.

That having been said, there is a light at the end of the tunnel at least with regard to development environments, and it certainly feels like Microsoft wants to have more devices in your home (rather than only in your office), so perhaps they will begin taking some of these problems more seriously, although we’re looking at years of development to solve them, so that’s immaterial for the moment.

For me, I tolerate the eccentricities and challenges of Windows because I want to open Photoshop and have it actually work when I edit images from my 30 megapixel camera, and I want all of that for less than $2,000, and Apple can’t give me that.

So yeah, Windows, overall, is pretty disappointing in 2020, but where it fails as an example of delightful, intuitive UX, it succeeds in running on top of commodity hardware that gives me the flexibility of components and cost to achieve what I want to achieve at a fraction of Apple’s premium.

You will have to decide what it is you want to achieve, and what you’re willing and able to spend to get it.